With the force of reason

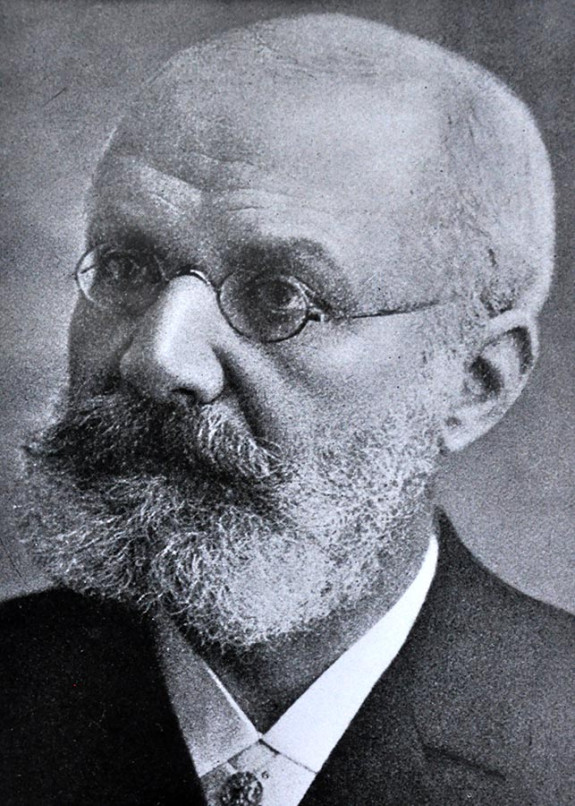

Harry Bresslau

- * 22.3.1848 in Dannenberg/Elbe

- ✝ 27.10.1926 in Heidelberg

Harry Bresslau was born in Dannenberg on the Elbe, a small city in the Kingdom of Hannover. He was the eldest son of Abraham Heinrich Bresslau, an emancipated Jewish merchant with full legal citizenship, and his wife Marianne, the daughter of Levi Heinemann, a royal banker to the house Hannover. Harry Bresslau enjoyed a good education and, looking back, described his parental home as well educated and liberal-minded. His father, however, left his family and emigrated to the United States in 1866 to begin a new life after the entire family assets were lost in the Austro-Prussian war. Bresslau‘s mother was left behind in a precarious situation to care for the two youngest children, Clara and Ludwig, aged seven and five. Harry, who at that time was 18, studied law for one semester in Göttingen before going to Berlin, where he studied history and philology and earned his living as a teacher.

In 1869, Harry Bresslau received his PhD from Georg Waitz in Göttingen with a doctoral thesis on the Chancery of Emperor Conrad II. Although he had a secure position as a teacher, he did not hesitate to follow the advice of his lecturer, Johann Gustav Droysen, to go on to attain a post-doctoral qualification in Berlin. As he records, it had always been his heart’s desire to pursue an academic career.

In 1874, Harry Bresslau married Caroline Isay, the daughter of a Jewish family from Trier. As a young married couple, they shared their rooms in Berlin with Harry’s younger brother and sister and two of Caroline’s nephews, both of school age. Bresslau earned his living at this time as a school teacher and lecturer at the university. Their living situation changed in 1877 as Bresslau received an extraordinary professorship. In the same year, their first son, Ernst., was born, followed by a daughter, Helene, in 1878 and their second son, Hermann, in 1883.

In 1879, the rising wave of anti-Semitism at the Berlin university found an outspoken champion in the historian Heinrich von Treitschke. This had negative consequences for Harry Bresslau, repeatedly causing him to be refused a chair in Berlin as professor ordinarius. For this reason, he followed a call to the professorial chair at the newly founded Kaiser-Wilhelm-Universität in Strasbourg in 1890, although the position was less well payed. In 1913, he retired into emeritus status at the age of 65 in order to devote more time to his new tasks as head of the section Scriptores at the MGH.

In 1918, following the German defeat in World War I, the Bresslaus were forced to leave Alsace, where Harry Bresslau had lived and worked for 28 years attaining high social status and academic renown. They first moved to Hamburg, where Bresslau completed his „Geschichte der Monumenta Germaniae Historica“ (History of the MGH), and then finally to Heidelberg, which was to be the last station in his life. There, he wrote an autobiographical contribution to the series „Die Geschichtswissenschaften der Gegenwart in Selbstdarstellungen“ (The historical sciences today in self-portraits) that was published in 1926, providing an invaluable source of information about his eventful life.

As a university professor, Harry Bresslau held his first lecture on diplomatics with particular focus on the charters of the German emperors, an area of study that was to become a lifelong pursuit. For his diplomatics research, he travelled to numerous archives throughout Europe and made use of photography to document the charters. Building on the ground-breaking work of Theodor von Sickel, Bresslau further developed medieval diplomatics to include the analysis of handwriting and dictation elements in the charters as well as the study of the medieval chanceries that produced them. To improve instruction in this field, he wrote a comprehensive manual on German and Italian charters, the first such systematic treatment of charter diplomatics. It became a standard work with the first edition appearing in 1888/89 and thereafter in a new, expanded edition from 1912 onwards. However, Harry Bresslau did not see himself as a charter researcher in the „strict sense“ in the way that Sickel did, but rather primarily as a historian. For him, the study of charters, just as that of medieval historiography, served the purposes of historical research in general. In this sense, Paul Kehr wrote of him in his obituary: „His interest in narrative sources and source criticism held his other inclinations [i.e. towards charter studies], which might easily have lead to a one-sided virtuosity, in a happy balance“ (Kehr, p. 252f.)

MGH editions

- Chronicon Suevicum universale, in: MGH SS 13 (Hannover 1881), pp. 61-72

- Die Urkunden Heinrichs II. und Arduins (Heinrici II. et Arduini Diplomata) (MGH DD regum et imperatorum Germaniae 3), Hannover 1900-1903

- Vita Bennonis II. episcopi Osnaburgensis auctore Norberto abbate Iburgensi (MGH SS rer. Germ 56), Hannover 1902

- Die Urkunden Konrads II. (Conradi II. Diplomata). Mit Nachträgen zu den Urkunden Heinrichs II. (MGH DD regum et imperatorum Germaniae 4), Hannover/Leipzig 1909

- Die Chronik Heinrichs Taube von Selbach (Chronica Heinrici Surdi de Selbach) (MGH SS rer. Germ. N. S. 1), Berlin 1922

- Die Werke Wipos (Wiponis Opera) (MGH SS rer. Germ. 61), Hannover/Leipzig 1915 (new revised edition of the edition of 1878)

- Die Urkunden Heinrichs III. (Heinrici III. Diplomata) (MGH DD regum et imperatorum Germaniae 5), Berlin 1926-1931

- Annales ex annalibus Iuvavensibus antiquis excerpti; Notae Aschaffenburgenses; Dedicatio ecclesiae Ardachrensis; Vita Lamberti praepositi monasterii Novi operis prope Hallam Saxonicam; Translatio sancti Alexandri in monasterium Hallense novi operis; Miracula sancti Columbani; Relatio aedificationis ecclesiae cathedralis Mutinensis et translationis sancti Geminiani, in: MGH SS 30,2 (Leipzig 1934), pp. 727-744; pp. 757-760; pp. 778; pp. 947-953; pp. 954-956; pp. 993-1015; pp. 1308-1313

Other selected publications

- Harry Bresslau, Jahrbücher des Deutschen Reichs unter Konrad II. (Jahrbücher der Deutschen Geschichte 12), Band 1: 1024 bis 1031; Band 2: 1032 bis 1038, Leipzig 1879, 1884

- Harry Bresslau, Handbuch der Urkundenlehre für Deutschland und Italien, erste Auflage Leipzig 1889; zweite Auflage: Band 1 Leipzig 1912; Band 2 Berlin 1931 (aus dem Nachlass hg. von Hans-Walter Klewitz)

- Harry Bresslau, Geschichte der Monumenta Germaniae historica im Auftrage ihrer Zentraldirektion bearbeitet von Harry Bresslau, Hannover 1921

- Harry Bresslau, Selbstdarstellung, in: Steinberg, Sigfrid (Hg.), Die Geschichtswissenschaft der Gegenwart in Selbstdarstellungen (1926), S. 28-83

Reference literature on Harry Bresslau